The Allure of Squid Game

Red Light or Green Light? Are We Condemning Violence or Revelling in it?

Sometimes nagging questions pop into my head just as I am on the verge of falling asleep. Did I turn off the lounge room light? Did I put the leftovers in the fridge? Did my child just finish the entire series of Squid Game?

As I ponder this, it occurs to me that with a title like Squid Game you could be forgiven for thinking it has something to do with the delightful and whimsical adventures of Spongebob Squarepants. After all, there is a cantankerous character named Squidward in that show complete with a big round bulbous head and rectangular pupils who works at the Krusty Krab. A hand drawn portrait of this lovable lout is currently hanging in my daughter’s bedroom at present.

Nevertheless, when it comes to the Korean, dystopian drama that is Squid Game, it doesn’t take long to realise that Spongebob, it is not.

Since its premiere nearly three months ago, Squid Game written and directed by Hwang Dong-hyuk, has been viewed over 625 million times. Fans from the very young to the old fogey alike, laud it as the best show Netflix has ever produced. It’s certainly their most financially successful. Almost overnight, the smash hit became a cultural lightning rod, entertaining, horrifying and even educating viewers on the pitfalls of economic disparities, greed and class politics.

A nine part series that stopped the world and made it squirm.

Not surprisingly, It’s not an easy watch (unless you enjoy having your fight or flight responses triggered at the outset). Imagine Alice’s White Rabbit down and out and eaten away by deprivation. A show that wants to lampoon us without drawing too much blood, so we’ll sign up for more.

I first found out about it through my eldest daughter and assumed it would be some sort of gorier version of The Hunger Games, with blood sport as entertainment. Or a seminal Piggy from Lord of the Flies volleying with his equals or betters in a dreamlike scenario.

Instead what’s on offer is an ultraviolent exposé of income inequality. A pretzeled universe with gore that is unapologetically Pollock-splattery.

But the squeamish needn’t run for the hills. Squid Game’s success isn’t solely down to viewers’ voyeuristic bloodlust.

What Squid Game brings to the table is an intensely thought provoking piece of television that is hardly shy about showboating viscera. 456 desperate people in dire straits play familiar childhood games and fight to the death in order to win 45.6 billion Korean Won prize money (around $38 million USD).

Stakes are raised continuously so the series is amplified above the highest level of inhumanity. Just when you think one game couldn’t be topped, along comes another to trump it.

Death is doled out by random functionaries (or in the first game, a robotic doll) and contestants run in cartoon panic. The moral compass here is lost and leaves one sick puppy.

Essentially poor people are killed for the amusement of the rich. A concept that could arguably be traced back to the heady days of the Roman Colosseum and gladiatorial combat. This series exploits this concept and throws gasoline on the whole mess.

It peppers a lineup of misfits who are essentially trying to make the best of a tough situation— The protagonist, Gi-hun a rascal so emotionally raw he’s like a walking wound; Sang-woo the smug overachiever, Deok-su a face tattooed gangster, etc — but the actors are given enough room to fortify each one with enough individuality for the many deaths to have meaning. So much so that your almost 9 hour investment is justified by a result that neatly rationalises the monstrosity of the whole affair.

There is a mentality to seize what can be seized or else not advance. Perhaps it’s embracing the countercultural ideals that we’ve allowed ourselves to become so jaded about.

So what really makes this series so alluring? Is it just violent entertainment to serve as a kind of opiate for the masses?

Sure Squid Game tends to go for the ugliest nuggets, but upon deeper inspection, the show is so much more than that.

The series is less of an exploration of modern pathology than a symptom of it. There’s a degree of intimacy here that transcends the script. We are forced to wrestle with the idea that infinitesimal odds of survival in the Squid Game might be better odds than the trappings of modern society. At least, modern Korea.

After all, surviving players are allowed to leave after the first bloodbath, but choose to stay as they need the money that badly. In this respect, human decency here translates to some form of impotence.

Gi-hun could be the reincarnation of millions of down-on-their luck plebeians who at last have learned to give as good as they get, or by necessity, better.

Essentially the belittled man sees only two possibilities: suicide or supervillainy. It is this stark division between the rich and the poor that represents the ugly truth of capitalism and makes us question how much we really care about the suffering of others. The desire and consequence of winning at all costs is painstaking to watch and yet the viewer of this series is told he is doing something virtuous by relishing the fictional death.

I think the magnetism for this series lies in the combination of enjoying vicarious horror while tut-tutting a system that would create such gruesomeness in the first place. The viewer is comfortably perched above the madness and feels safe to root for the take down whilst revelling on the show that’s on offer.

It is like it’s trying to be both scathing and healing at the same time. A vintage of a very particular sort that hinges on the veldt between political commentary and murder that is fetishized.

According to show director Hwang Dong-hyuk, it may be a peculiar mix of nostalgia and morbid intrigue: “People are attracted by the irony that hopeless grownups risk their lives to win a kids’ game. The games are simple and easy, so viewers can give more focus on each character rather than complex game rules.”

One thing for sure, we live in a time when the border between parody and reality feels agonisingly thin.

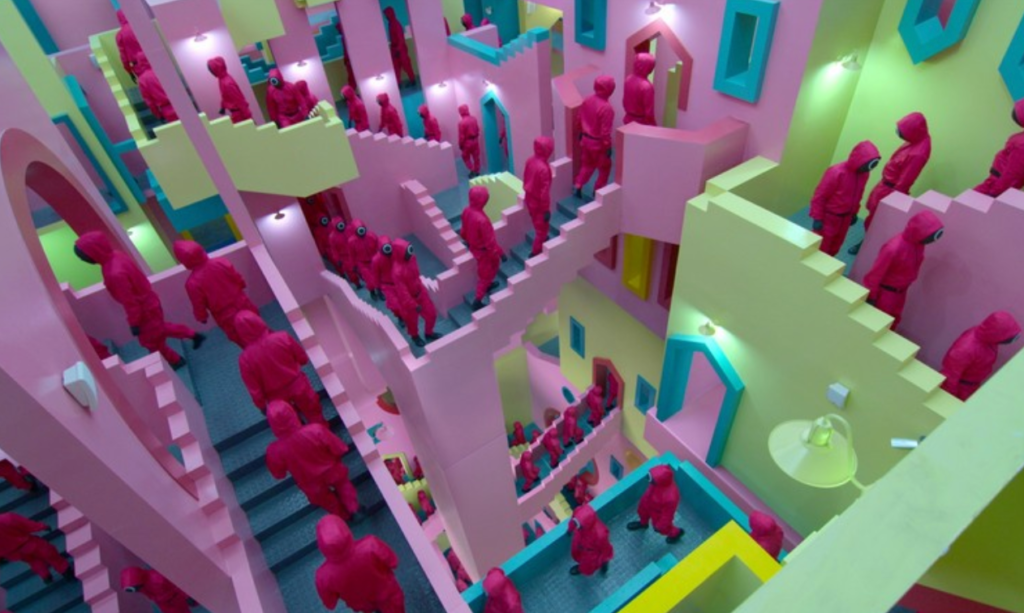

From a production standpoint, there is much to admire here too – including the granular detail provided in a set that’s cardboardlike with harlequin hues. It’s a highly stylised visual splendour.

No doubt these fussy trappings and the nostalgic visual palette of a Korean niche culture only adds to the appeal. Plus Hwang Dong-hyuk’s direction is so tight and intimate, that you root hard for the sequence to work.

In many ways Squid Game is reminiscent of the class division in Parasite that won Best Picture at the Oscars in 2019. Both offerings present explosive plot grenades that leave you reeling long after the credits roll. The difference is that, in Squid Game, players are given the choice to play.

Ultimately they do, because this life-or-death tournament is nothing compared to the misery of their real-world existence. Surely, it’s a sad indictment when desperate people have nothing else to offer, except their lives.

The question will always debate whether splattery satires like Squid Game are purgative or inflammatory. The answer, of course, is that they’re both (which makes me watch them at arm’s length). I’m torn down the middle, but that exposed middle is where the horror genre plants its seeds.

Nonetheless, Squid Game is somewhat sentimental with twists that work thunderously well and a tightly written script.

There’s no baroque innocence over the games that are played. It ain’t child’s play. At a base level, it’s a rare Netflix binge that never sags. It’s also incredibly graphic – which might account for its huge popularity among game-savvy teenagers (who have now likely acquired a taste for K-drama – subtitles and all and will undoubtedly sign up for more).

It should be mentioned that the series is designed for mature audiences only as the themes are clearly dark and the young would fail to grasp the irony and political satire that underscores the premise (plus the many bullets to the brain may induce a nightmare or two).

Regardless of Squid Game’s lure, surely we should reflect on the reality of our relationship with violence as entertainment. We should consider the commentary made on wealth inequality, capitalism, honour, justice and survival at all costs. As viewers we are all implicated whether we watch it in horror or in delight and the deprivation on offer here should be the disease otherwise it’s our voyeuristic pleasure.

In the end, are we condemning violence or revelling in it? Perhaps we’re unapologetically doing both. Either way, Squid Game is a parable for people who know how to live in a world that is black and white, but still dream in blood red.

What are you thoughts? Please drop me a line and let me know why you think Squid Game is such a successful hit and whether it is worth all the hype. Are we condemning violence or simply revelling in it?

Also please note that I DO NOT endorse Squid Game for children. It is simply not suitable.

I am a writer and one of my favourite things to do, are film and television reviews. Hence I wrote a review about this series as it was the last series I watched and I wanted to add my ‘two cents’ on what I think all the fuss is about.

As parent myself I like to reflect on what I am watching and what my children (older or younger) are watching too. It allows for meaningful discussions. Articles like this allow me to articulate my thoughts and stretch my literary creativity into the review writing genre.

So, if you like this article, please share and or comment below. I do appreciate the support as it allows me to continue to do what I love – writing!